No products in the cart.

Blog, potato (Solanum tuberosum)

Potato Towers Don’t Work

Overview

Overview

- Potato towers are a form of extreme hilling that uses a structure to add a foot or more of soil above the seed tuber.

- Towers are not a new idea, but they have only become popular in recent years.

- Potatoes are normally hilled up about six inches, whether they are grown in the ground or in containers.

- Hilling up much beyond six inches brings no benefits and is likely to reduce yield.

- The purpose of hilling is not to stimulate production of tubers, but to protect the tubers from the environment.

- Potato yield is primarily limited by foliage area, not by the amount of soil above the seed tuber.

- Indeterminate (late) potatoes do not form tubers in a different way than determinate (early/mid) potatoes. They just grow longer.

- Conventional container growing works fine with potatoes but potato towers don’t work.

Introduction

You have probably read about potato towers somewhere on the Internet. The idea is immediately appealing: rather than strain your back growing potatoes in the ground, you can grow just one plant, but keep adding soil to it in layers to increase the yield. This is essentially extreme hilling, adding 12 to 30 inches or more of soil over the top of the seed piece instead of the more typical 4 to 6 inches. Each additional layer delivers roughly a doubling of the yield versus growing the plant in the ground. At the end of the season, you just take the tower apart and hundreds of pounds of perfect spuds tumble out at your feet. The only problem with this idea is that it isn’t true. You will find no research that supports this idea. You will also not find any photographic evidence that is not obviously faked. The claims about the physiological basis for this idea are totally wrong. Despite these limitations, the myth persists and grows stronger each year. Nathan Pierce, a moderator for the Kenosha Potato Project, called the potato tower phenomenon “the single worst piece of gardening advice that you see frequently on the Internet,” and although the Internet is chock full of terrible gardening advice, I think he is probably right because towers require a substantial investment of time and material that brings no benefits. This post will take a look at the history of this idea and delve into the reasons why it simply doesn’t work.

Defining Failure

Before we go any further, I want to clarify exactly what I mean by “doesn’t work.” I always get some angry responses when I claim that towers don’t work. I am not saying that you can’t grow potatoes in a tower or even that you can’t get good yields in a tower. I am saying that you won’t get better results with a tower than you can obtain under similar growing conditions without the additional levels of hilling. You will almost certainly get worse results with a tower if you do perform all that additional hilling. (Growing conditions vary, and in some climates it might still work out for you, but it will be success in spite of your efforts.) It is specifically the claim that towers are able to produce greater yields due to the production of more layers of tubers that is wrong. If you take that away, then a tower is just a planter and subject to all the pluses and minuses of growing potatoes in containers, which are specific to climate.

Several people have asked, quite reasonably, how we could tell if a potato tower worked as described. I don’t want to get your hopes up, because there is really no possibility that you are going to find success with this, but it is still a useful exercise to imagine what it would look like. Per plant yields with elite potato varieties occasionally reach 10 pounds or more under perfect conditions. If a tower worked as described, it would be able to routinely exceed that threshold. The tower hypothesis claims that the additional hilling allows the plant to create more tubers, so the tuber count should also be significantly higher than for a conventionally grown plant. If you can show this kind of high yield, high tuber count combination and you can reproduce it reliably, you might have the first real tower potato. Just don’t invest your retirement savings in this project.

Wire Mesh Towers

There is another kind of tower, made of wire mesh, where the plants grow out the sides. I am not discussing that type of tower here. It is not as obviously incompatible with potato anatomy, but it seems most people don’t have great results. I wouldn’t expect great results, since this kind of structure takes a plant that normally forms stolons over 360 degrees and reduces that to about 150 degrees. Half of the tower is always going to be shaded, so that further restricts the yield. You are trying to overcome the plant’s natural geotropism. It is going to find a way to send shoots upward against gravity and roots downward with gravity, no matter what you do. People think that the roots will go to the center of the tower, but geotropism says that the roots are going to grow mostly downward along the outer wall of the tower, where water and temperature management will be challenging. So, I have serious doubts, but I haven’t tried this kind of tower and don’t plan to, so I will reserve judgment.

Where is the Research?

I get a lot of responses to this post and one question comes up again and again: where is the research that shows that potatoes don’t form additional levels of stolons? As far as I am aware, this has not been studied. There is a good reason for that. Nobody has observed a potato that grows this way. It is kind of like asking why there aren’t more studies showing which tomato varieties form tubers. Nobody has studied that because nobody has ever observed a tomato that makes tubers. Science usually starts with an observation. It would be better to ask if there is anybody who has documented a potato that does form multiple levels of stolons. This would be very easy. Just one picture would sort everyone out and almost certainly inspire further research. I have grown tens of thousands of potato plants, from hundreds of accessions, modern, Andean, and wild potatoes from the whole native range of the potato. I have never seen one that forms stolons in the way that is imagined in towers. I have also talked to many other people with similar experience who have never seen such a thing. You can’t prove that something doesn’t exist, but you can prove that it does. I leave it to boosters of the potato tower to demonstrate a variety that behaves in the manner claimed.

There are several studies that conclude that hilling increases the marketable yield of tubers, but not the total yield. That shows that hilling is protective. It primarily protects the tubers from sunlight, but also pests and some diseases. This means that more of the tubers are in good condition for sale. The total yield is generally the same though.

Quite a few people have also pointed out that there are university Extension articles that promote towers. The Cooperative Extension System is a great idea – bringing growers into contact with scientific experts to get the best possible information. Unfortunately, it is also not what it used to be and a large number of articles published by local Extension groups are written by non-experts. Several Extension articles that I have reviewed on this subject were written by people who clearly did not have experience with potato towers or much experience growing potatoes for that matter.

History of a Bad Idea

People have been growing potatoes for 10,000 years. They formed the backbone of Andean agriculture and the native peoples of the Andes were no slouches, as attested to by their massive earthworks. They terraced valleys from top to bottom, built canals to carry water through the mountains, and possibly even built agricultural experiment stations. The later adopters of the potato were no dummies either and were unusually driven to increase crop yields, leading to the Green Revolution. Somehow, none of these people figured out how to grow potatoes in towers. You would think that, if this worked so well, there would be large scale installations of potato towers all over the world.

From Tires to Towers

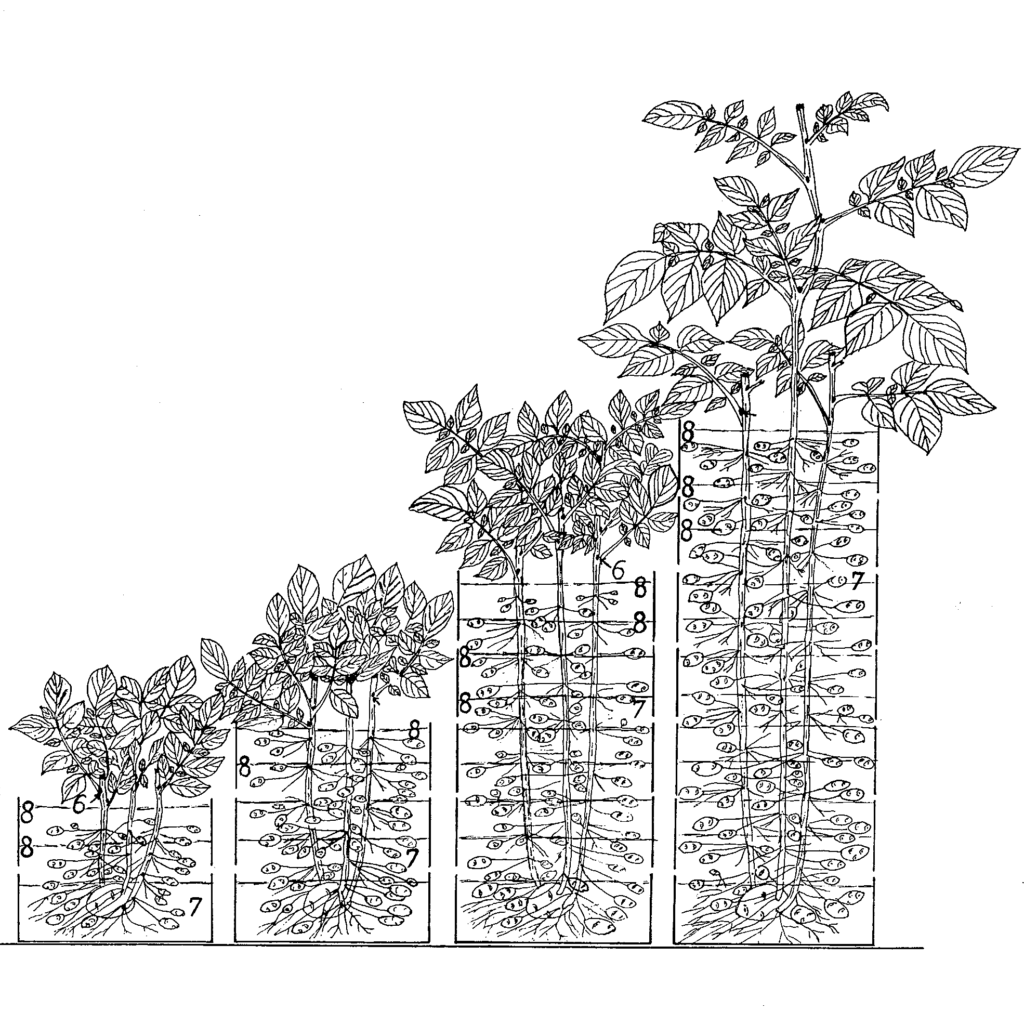

As far as I can tell, the potato tower began with the idea of growing potatoes in tires. Somebody realized that you could achieve the necessary hilling quite easily by putting a potato on the ground and then filling up the tire with soil. That works very nicely. I’m sure it didn’t take long before someone decided to add a second tire, then a third, and the tower was born. I’m not sure how far back that idea goes, but I’m guessing that just about as long as there have been tires, there have been people trying to grow stuff in them. I can find references to growing potatoes in tires going back to the 1970s. References to towers don’t go that far back, but some structures that we would now call potato towers do. The most notable of these is a potato tower patent from 1976, from which I lifted the image above. While the patent predates the term “potato tower,” all the elements are there and the illustration does an admirable job showing a kind of potato growth that has never been captured on photo or video. One of the most fascinating parts of the potato tower phenomenon is how little people are deterred by its lack of reality. There is more than one patent for potato towers and hundreds of articles, both in print and on-line. A lot of work went into writing all that material, but apparently no testing. That’s pretty remarkable.

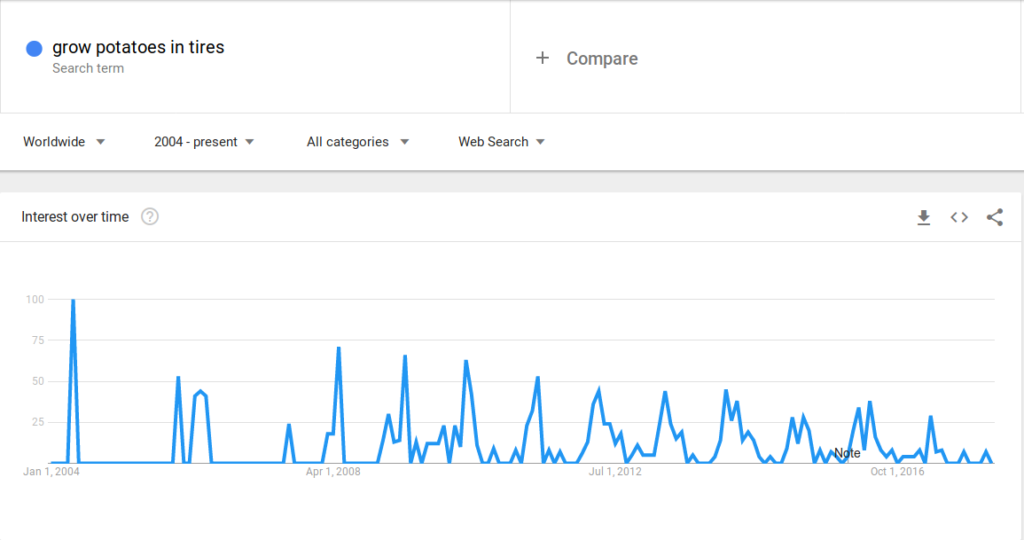

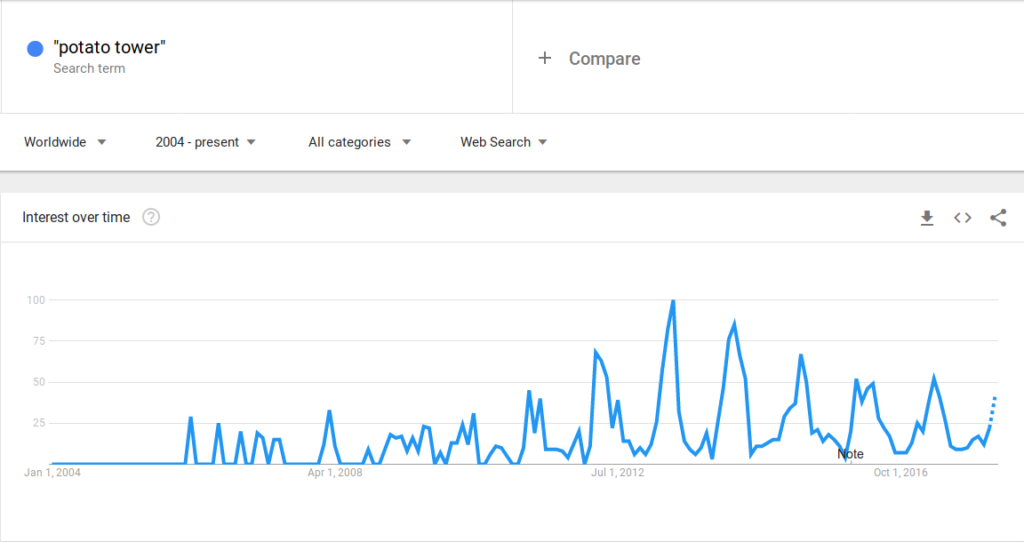

The term “potato tower” first started to show up on the Internet on Usenet in the 1990s, but it wasn’t a common term. Through the 1990s, there are more than a hundred mentions of growing potatoes in tires for every mention of potato towers. Potato towers came into the Internet consciousness in 2006 and really started to take off in 2012. Google Trends shows the frequency of these search terms over time:

So, fewer people are searching for information about growing potatoes in tires, but more people are looking for information about potato towers. While spring searches for the term peaked in 2013, the overall amount of searches year-round have been pretty constant. It doesn’t look like the potato tower myth is ready to die out on its own, unfortunately.

The Irish Eyes Type Tower Box

For the first few years, the idea shows up primarily in forums and personal blogs, but starting about 2005, it began to creep into magazines and newspapers as well. One frequently cited article from the Seattle Times in 2005 (followed by a more popular recycled version in 2009) promises 100 pounds of potatoes in four square feet. This idea traces back to Irish Eyes, a seed potato supplier, and appeared in newspapers across the country over several years. In fairness, the article reports that someone who tried it produced only 25 pounds. Assuming that they planted one tuber per square foot, that would be a yield of 6.25 pounds. That’s on the high side vs. the typical field yield, but still well within the possibilities for growing potatoes in the ground. This is one of the common results that you see with towers: people are very impressed with the yield, even though it is not any better than they could have expected if they grew plants in the ground with the same level of attention.

Other than being taller than necessary, the Irish Eyes box (see right) is a reasonable enough design and the yield promises are not impossible, although few people are likely to achieve them. By allowing the plants to grow out over the sides of a 4 square foot box, you can really expand the foliage area to around 16 square feet. (But bear in mind that you could easily grow 16 to 20 plants in 16 square feet of ground.) If you live in a perfect climate and put the plants on drip irrigation, you could possibly grow 13 plants in that box – 9 along the perimeter and dangling out and four growing in the center. 100 pounds divided by thirteen plants gives 7.7 pounds per plant. Very few people are likely to ever see such a high yield, but it is within the range that can be achieved growing in the ground, everything else being equal. A Denver Post article supplies a bit more information, including the fact that the originator of this idea has achieved a maximum yield of 81 pounds. That would be 6.2 pounds per plant, still a great yield, but well within reason in the most favorable climates.

The main problem with this design is that it is much more elaborate than it needs to be. There is no reason to build it up so high. The multiple levels would lead you to believe that what happens inside the box will look a lot like the patent illustration at the beginning, with tubers forming at every level of the box. That just doesn’t happen. If you grow a potato like this, when you dig it up, you are going to find a very long stem and a cluster of tubers at about the level that you planted the seed piece. This is really just an unusually tall planter. You could do as well with a container of the same area that is only about a foot tall.

The Modern Myth

I think that we have found the origin of the modern potato tower concept, but it had not yet reached the point of unbelievability So, when did this thing go fully fraudulent? It is actually pretty hard to pin it down. Starting in 2009, there were hundreds of blogs and articles per year about potato towers, offering a spectrum of variations on the story. I read dozens of these articles and I would have to do a lot more work to establish the timeline. It isn’t worth the effort. One thing that I feel pretty confident about though is that most people did not set out to tell a tall tale (so to speak). This story evolved over time, with people adding a few details here and there that they thought plausible. If you can fault most of the people who have written about this with anything, it is not sufficiently testing the idea before promoting it. Articles about potato towers fall into four categories: those that promote the idea and never report on results, those that later report pretty normal potato yield, those that later report failure, and those that promote the idea and then unconvincingly report success (usually in support of selling a tower kit).

The tower story has gotten a lot more refined over the years. It now includes details like the need to add levels at a certain rate in order to force the plant to form more stolons and a requirement for indeterminate varieties in order to produce multiple levels of tubers. Many sources now claim that potatoes won’t produce stolons over a long expanse of stem, but “only” about a foot. If you have a potato that produced stolons over a vertical foot of stem, please take a picture! I won’t hold my breath waiting for my inbox to fill up. These enhancements sound good and they might convince you that, if your tower didn’t really work, it is because you didn’t do it right. It isn’t your failure though. The whole idea is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of how potatoes form tubers.

Potatoes Just Don’t Grow Like That

We could spend a lot more time looking into the origins of the potato tower, but let’s cut to the chase. Potato towers don’t work any better than growing in containers or growing in the ground, all else being equal. All else being equal means that they get the same kind of soil fertility, the same soil temperature, the same amount of water and drainage, the same amount of soil coverage, and the same level of defense against pests. Often, it is easier to achieve these things in a container, although sometimes the opposite is true.

There are two insurmountable problems with the potato tower concept:

- Tuber production is limited by foliage area.

- Domesticated potatoes don’t produce additional stolons past the first few nodes above the seed piece.

We could dispense with this idea based only on the relationship between foliage area and the total energy budget of the plant. The main function of a plant’s foliage is to collect energy. That energy is converted to sugars and moved into the body of the plant for storage. This is where tubers come from. They are little balls of captured energy and water. Evolution does not allow for slackers. Plants have evolved to fully use the capacity of their leaves to capture and store energy. There is no excess energy for the plant to use to form more tubers, no matter how many stolons that you might convince it to produce. If you somehow forced the plant to produce ten levels of stolons, then you would get 10 times as many tubers that would be 1/10th as large (actually less, because so much energy would have to be expended on the formation and maintenance of all those stolons). If you want more yield, you need more foliage. Nobody claims that towers produce more foliage though.

The other problem is that potatoes simply don’t produce an endless number of stolons. Stolons are formed from the first few nodes above the seed piece and rarely any higher. The reason for this is that the plant forms stolons in response to available energy. While there is no technical limit to the number of nodes that may form stolons, tubers forming on stolons at the lowest nodes will soak up the available energy and prevent the plant from forming tubers on higher nodes. You can force a plant to form higher stolons by removing tubers, but this obviously has no practical value. Hilling up in excess of six inches is a waste of time and effort and only makes the plant work harder. The reason for hilling is not to make the plants form more tubers but to ensure that the tubers are covered by soil. Tubers need to be covered to protect them from pests, diseases, and sunlight, which will turn them green and increase the content of toxic glycoalkaloids. Plants will often survive extreme hilling, but you aren’t doing them any favors; they have to pump photosynthate and water farther, which costs the plant energy. The greater depth of soil can also be a barrier to water reaching the roots.

It is worth spending a little time thinking about the purpose of potato tubers. Perennial plants often form large storage roots as a reserve. The water and carbohydrates that are stored in the roots can be used to sustain the plant through difficult conditions or to allow the plant to survive the winter when the aerial part of the plant is killed by frost or drought. The roots are sometimes formed deep in the soil in order to achieve the maximum level of protection from the elements. Potatoes are annual plants. Even in a frost-free climate, they eventually die back and the original plant does not regrow. So, while tubers can act as a reserve, particularly while a new plant is getting established, they are primarily a reproductive structure. Potatoes naturally form their tubers just below or even at the surface of the soil, with stolons also running just beneath the surface and often emerging to form new satellite plants. We plant them deeper or hill them to protect the tubers from exposure and also to prevent the stolons from forming additional stems instead of tubers. Left to its own devices, a potato plant spreads horizontally, forming a combination of secondary plants and tubers. It never grows deeper into the soil. Given that, it is easy to see why potatoes haven’t evolved the ability to set additional layers of stolons from a deeper planting. Only humans plant potatoes deeply.

Indeterminate Potatoes

A mythology has been built around the idea of the indeterminate potato as the solution to the tower problem. Indeterminate potatoes do not produce stolons in a different way than determinate potatoes do. It is also worth pointing out that determinacy is not really a very useful concept with potatoes; it is essentially a more complicated way to express whether the maturity is early or late, unless your main interest is in the flowering behavior of the pant. Potatoes form all the incipient stolons that will become tubers in the two to six weeks following emergence. While early/determinate varieties form a certain amount of foliage, flower, and then die back, late/indeterminate varieties continue to branch and flower for a much longer period of time. The tubers and the total yield are often larger, but this is simply a result of the plant having more foliage area and more time to grow. A tower adds nothing to the experience of growing late/indeterminate varieties other than additional work.

Breeding a Tower Potato

It is possible that a variety could be bred to better take advantage of the vertical space provided by a tower, although I don’t think it is likely since the tower introduces a lot of additional problems that must be overcome. Some late domesticated varieties and wild potatoes set stolons over a larger number of nodes and also can form very long and sometimes branching stolons. These might be convinced to grow through a larger vertical space. Potato plants also vary considerably in size and a much larger plant would be able to collect more energy. In combination, these traits might make for a potato that would behave more like the tower potatoes that have been imagined. Even if it is possible though, it doesn’t seem like a very practical investment. One limitation is that you will always need the oldest tubers to stop growing to allow for newer tubers to form. That means that any plant that successfully forms more layers of tubers will do so at the expense of tuber size.

Conclusion

The great thing about potatoes is that they are simple to grow. And cheap too. Why make it complicated and expensive? A simple container or raised bed, filled with quality soil, amended and watered appropriately, can deliver heavy yields of potato along with the other benefits attributed to towers such as easier management and harvest. Potato towers don’t work. They never did and they probably never will. No doubt, the idea will persist on the Internet as long as people still grow potatoes, which will probably be a very long time.

As of 2020, this article has become the most popular on our website. That doesn’t appear to have made much of a dent though. Towers are more popular than ever. There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch, but that has never stopped people for searching for one.

Have you tried a potato tower? If so, leave a comment and let the world know how it worked for you.

More Information

The Low Technology Institute is studying several different potato growing methods this year, including towers. If you are interested in this subject, you might want to follow along.

Nathan Pierce, an admin with the Kenosha Potato Project experimented with towers for several years and documented the process at Tomatoville with lots of pictures.

Hey Bill, Great post. I’ve got a copy of “the Self Sufficient Gardener” by John Seymour, and there’s a sidebar illustration of this method, I think with the potatoes growing in a barrel. It definitely seems to be a fully realized version of this meme, and I suspect is was thrown in as an afterthought. The entire book seems to be a (beautifully illustrated) mish mash of different gardening systems and tips and tricks thrown together to capitalize on his self sufficiency superstardom (at that time I think the late 70s)

I think its also worth mentioning how much hotter and drier the soil is going to be in a tower vs in ground, and how much potatoes hate to have their root systems at high temps.

Thanks Tim. That’s very helpful information. I will likely revise this article at some point and knowing more of the historical details will make it easier to track down the origin.

The topic of growing potatoes in containers is pretty complicated, which is why I didn’t go into detail. Because they so dramatically change soil temperature and moisture levels, considerations for container growing are tightly coupled to climate. The problems that I have with growing potatoes in containers are likely to be very different than those that you experience.

Not only I totally agree .. I study how well vines grow tubers vertically (almost 10 years now)! Different strains may bulk tubers set on nodes further away from the seed piece BUT I have no evidence of any decent size tubers above 14″

THEREFORE any container taller than 16″ is a complete waste of time.

I’m glad that the Kenosha Potato Project is linked from your name Curzio. People who are interested in towers should really check out the KPP, because growing in bags offers a lot of the same benefits but without the hyperbole.

Thank you for this article.

My observation is the same. I have tried additional hilling via cages and bins. I have not observed a significant difference in yield between light hilling and extreme hilling of potatoes. Your article is well written and covers the lack of available science, plant biology, history of the myth and much more.

Well done!

Interesting. What if we planted 2 plants 6″ up to 20 ” then at 20″ up rotated 90° and planted 2 more to go to 36″ that would not only be great looking but provide an additional layer for the potatoes to grow well?

Thoughts?

The problem is moisture management. If the soil is permeable enough for the water to get to the bottom, it won’t stay in the top layers long enough. The container will be dry at the top or the bottom and those plants will suffer. You could perhaps engineer a solution to that, but you are now expending lots of effort to grow plants that are otherwise quite simple to grow in the ground.

I have tried to grow potatoes in a tower three times. Only the last time did I achieve any sense of success but it simply reflected what you stated in your article. One layer of potatoes and a meager harvest. I also attempted to grow them in the ground to no better success. Fortunately, I am better at growing other crops and will stick to them in the future. I fo, however, have a question. Sweet potatoes are grown from rooted sprouts as opposed to planted eyes. Do they grow the same way?

Sweet potatoes don’t really grow in this climate, so I am not an expert on the subject. We’ve had a discussion about this in the Cultivariable Facebook group and it sounds like the same basic ideas apply. Sweet potatoes can have longer vines and more foliage area, but if you don’t let it spread out to catch sunlight or trellis it in some way, you won’t get the benefits.

I had been interested in the towers, to cope with limited garden space but also to avoid a lot of fruitless digging for that last potato. Some experiments on Youtube bear out what you say; they get a layer of spuds at the bottom, a lot of empty soil in the middle and then foliage out the top.

As a modified container, this year I am going to try rolling a piece of linoleum into a ‘tower’ and plant in the middle of that (without needless vertical addition), just to make harvesting easier on my back. I’ll do a side-by-side comparison with traditional in-ground planting.

By the way, I had also learned to do potatoes on the surface, under a thick layer of straw (what the French here call ‘paillage’) but the crop was terrible compared to my standard beds in the same soil and same weather. And I visited a nearby permaculture project with the same experience, so ‘innovation’ is not always helpful.

Straw can work, but it is very dependent on environment. Conditions can’t be too wet nor too dry and if you have rodents, they can become a big problem. My experiments with growing under straw have produced more voles than tubers.

Yes, both rodents and excessive moisture probably played a part in my poor harvest from the mulching bed.

Biil and everybody !

Thank you so much for good informations and experiences on potato tower.

I like intorduce to students and hobby gardener.

I can attest to everything (first hand) you have explained and described in your article. I too fell into the “tater-tower trap” that is so pushed all over the internet. I had been using these 36″ tall towers for the last five years and generally speaking would only average fifteen pounds per container. The tubers only grew in one layer of soil as you described and adding soil would generally hinder the growth of vegetation. In addition, adding more tubers in subsequent layers of soil (filling the tower) rarely grew more potatoes by the time they were ready for harvest.This practice also required a lot of watering to reach the lowest level of tubers and a large amount of soil handling. Growing potatoes in the traditional method (in the ground) resulted, at least in my case, in higher yields that the towers did. My goal in using the towers is to grow more vertically due to my limited garden space.

Thanks to reading and learning from your enlightening research, I have since cut my towers in half (now 18″ tall) and just planted my potatoes a few weeks ago…anxious to see the difference this year. What I feel is most beneficial, is the fact that you are willing to share your knowledge and expertise as you have with others! Thank you very much!!

Reporting back regarding my previous post dated April 29, 2018…..

My last entry stated that I had cut my 36″ towers in half (now 18″), due to the fact that the (Internet promoted) “tower” method did not work. So now I have doubled my containers from two to four, and considering the tubers only grew approx within ten inches of soil, in reality I had doubled my growing capacity. After a full (2018) summer growing season to now be able to make a comparison, I can say my yield not only doubled, but tripled when you consider the volume of unused soil I was filling these towers with. My containers are approx 48″ in diameter and each one had a yield of nearly 20-lbs. All four of these “half towers” were planted with assorted varieties of fingerling potatoes. I keep these containers up in my garden throughout the winter, augment the soil with organic matter, and they’re ready to go in the Spring. If I hadn’t found the Cultivariable site I’d probably still be trying to figure out what I was doing wrong!!!

Thank you your two very detailed comments. My last veggie garden was back around 2000. I’ve been slowly searching online to brush up my knowledge to start a raised veggie garden next Spring. I was set to build a potato tower until finding this article.

Your specific comments were very helpful. Congratulations on your higher potato yields. Cheers!

Rio, glad you found it helpful…happy to share my experience and all the best with your garden!!!

Hi Curzio, I experimented the potato tower two years ago, expecting a total failiure. Surprisingly it worked ! I did not obtain the 100 lbs promised but let’s say a fair 22.5 lbs from 5 small potato planted. What amazed me was that I got potatoes from bottom to top, at 44 inches from the ground !The biggest of them were situated near the surface and were even turning green due to sun exposure. Many tubers were attached directly on the stem, especially those near the top. The variety used was Kennebec. So, yes some varieties do produce tubers quite high on the stem if they are burried. You can see the results on my blog. The blog is written in french but you can look at the pictures.

https://jardincooldotcom.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/tour-a-pommes-de-terre-recolte.png

Thanks for the Feedback Marc! (Although I am not Curzio. ;) )

As noted in the article, you can grow perfectly good potatoes in a tower, you just can’t expect to grow more than you would in the ground if the soil were of the same quality. 22.5 pounds from 5 plants is 4.5 pounds per plant, which is a good yield, but one that is fairly easy to achieve in good garden soil with sufficient fertility.

As a rookie, last summer I was excited with the idea of making a miracle harvest with a potatoes tower. I therefore went on and tried to build one. I ends up with 3 to 4 feets of filling. I dreamed all the time that my tower is filling up with potatoes. Just to be horribly desapointed. After I tipped over the tower, I had only long stems, a handle full of potatoes at the seed level. Nothing else, no miracle. I even noticed that the seed level was relatively dry, this as a result negatively impact my yield.

I hope did my home work before trying, I but I learned the hard way, potatoes tower does work.

I am however wondering whether planting seed at different levels of the tower would make sens.

I wish I red this article before hand.

Hi Bill,

We’ve completed the research and guess what: the towers didn’t work in our controlled study! I’ve got a full write-up of the different methods here: https://lowtechinstitute.org/2018/12/04/potatoes-five-ways-a-trial-looking-at-different-potato-growing-methods/

Feel free to use this any way you like as long as we’re cited. Perhaps our poster is useful: https://lowtechinstitute.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/moses-poster-scottjohnson.pdf

I did some research into the towers over the year and I think I figured out a way that I could force them to work, but I have to test this out this year. First, as you probably know, potatoes form on “runners” that are put out during the third phase of growth (same time as the flowers). Therefore, any filling of a potato tower after flowering will never result in deeper layers of potatoes — the plants don’t produce tubers on stems after the flowers are seen. Therefore, if one uses a tower and really aggressively fills it up so the plant has, say, two feet of fill before it is allowed to grow tall and flower, perhaps — PERHAPS — the stem could produce tubers up that entire length. I’ll try this this year, but it seems like a really persnickety way to grow them.

This does not work either. What happens is that the plants exhaust themselves trying to climb out of a constantly increasing soil layer. They essentially have no energy left to product tubers, so it is actually counter productive to do this. I’ve tried it with several varieties, including some long season and intermediate types.

Most commercial potatoes also do not set tubers on runners. They set tubers in a single location, and at a single depth (both of which vary by variety). They have been bred and selected to do this to make mechanical harvesting easier. That is the opposite of what many people who are trying towers want, making the vast majority of commercial potato varieties very poor for deep containers.

You can grown them in containers, but limiting the height is the key to getting decent yields, and it should not be expected to get better yields than when grown in the ground, which is where potatoes have evolved and been selected to grow for thousands of years.

But you didn’t backfill the potato bag with soil?

You used straw?

When you trenched and filled you covered with soil so why wouldn’t you do the same with the bag?

I was hoping to see a conclusive result but you’ve not followed the standard potato bag growing method of backfilling with soil as the plant grows taller.

Backfilling with straw is a difficult method to get right as it is affected by how wet the straw becomes.

I’m guessing you recommend containers that hold moisture but with good drainage? And that chicken wire would be too porous and prone to drying out quickly? Can you write about potato bags and what you recommend?

This depends largely on your climate, but I suspect that most people would find growing in wire cages difficult. I’m not an expert on growing in bags, but Curzio Caravati of the Kenosha Potato Project has done quite a bit of experimenting with this. You might want to check out the KPP on Facebook.

Thanks. I’ve looked at the Kenosha Potato Project quite closely, and have opted for grow bags.

Oh. I thought you were supposed to plant a new seed tater at every level, not that they were going to spontaneously generate new tubers just because you covered them in dirt. Never cared, never looked into these towers really. I grow only produce that’s actually expensive to buy, and you can get like 100 lbs of spuds for $10. Just not worth the time and effort unless you’re actually growing for sustenance innawoods somewhere.

I have tried towers with no luck, then had an idea. What would happen if I built a tower that was shaped like a ‘dunse cap’. I used wide spacing wire and built it up using straw as the wall and compost in the center and planted potato’s on the outside edge every 30 odd Cm all the way to the top. Potatoes poke out the side and I finished up with potato’s all the way from bottom to top.

What about a tomato in the tow wer? An old guy told me to bury the tomato deep n keep adding soil. You get a huge trunk n more tomatoes. I’ve burried deep n got bigger stalks or trunks, but haven’t noticed more production.

My father recommended this specifically for more stability for a transplanted tomato plant, to prevent the stem from breaking on a top-heavy purchased plant, not to increase production on a plant. Burying it deeper encourages roots to grow from the buried nodes, not to produce any more flowers.

All I know is that my grandfather was the best gardener I ever knew and he used the tower method with great success. He operated a small farm for both feeding his family all year long and for profit and he wouldn’t waste his time on something that wasn’t worth doing.

As I mention in the article, insofar as a tower is a container, they work fine. In many places, the soil may not be well suited to growing potatoes and they will do better in a container. But the main feature of towers – putting on additional levels of soil – definitely doesn’t help. So, many people have what they consider to be good results in towers, but that doesn’t mean that they would not have better results, with less effort and expense, by leaving out the additional levels of the tower.

Except only stupid people are building a tower for one plant.

I don’t know that I would call anyone stupid for following widespread advice that many people swear is effective. That’s the reason why this post exists. You’re not stupid the first time that you follow bad advice.

I thought the whole point of the potato tower to allow more plants to grow in the same horizontal area, by letting them poke out the sides.

Doesn’t that make the article a…haha…*straw*man argument? (Yes, I replied for the pun!)

Putting aside that potato towers aren’t effective for increasing yield, I’d like to focus on the fact that potato plants survive the process of having their shoots repeatedly buried while the potato is towered, without complaint save for exhausting the energy stored in the seed potato. My question is whether or not other Andean root crops e.g. mashua, oca, and ulloco would also survive this process, again ignoring for the time the general condemnation of the practice.

I haven’t tried it, but I expect that they would. In field agriculture, these crops are typically hilled, ridged in the same way as potatoes. The advantage of a tuber is that it has lots of energy to keep pushing up a sprout through as much soil as necessary, where a tiny seed would eventually be exhausted.

Gosh Darnit, why didn’t I see this article before I wasted time, money and materials making a fricking potato tower!? I suspect I am not the outlier who is going to magically succeed at this so now I will simply have a lot of useless dirt and a normal (hopefully) crop of potatoes. :(

Well, at least you read it before you built a second one! It will still make a fine planter.

Great article, but I still wanted to try the experiment myself;

https://youtu.be/gcQ3whdBpCI

I’m looking forward to comparing results from the 3 experiments.

So glad I found this article. It explained all the struggles the plants seemed to be going through as I proceeded with the directions for potato towers. I attempted the potato tower (using a few sweet potatoes rather than potatoes because our climate is quite warm and dry). I was able to get some greens, but they were long and scrawny, and gradually more diseased looking. Every time I added soil or straw, about a half of the greens would rot! I had watched a homesteading video that made it look like magic, but sadly, I ended up with withered greens, rotted greens, no sweet potatoes, and LOTS of widow spiders. I live in zone 8a, where the temp is between 85-106 in the summers. I used three types of sweet potatoes to start, along with straw and potting soil placed in layers in a open topped 3’x3’x3′ wooden box lined with ground cloth for drainage and a front door wired closed, (with the hope that I would open it and the sweet potatoes would come rolling out). I had it in full sun for about 4 hours a day. It was a complete failure. It is so dry here that rot is rarely something to worry about, and pots and grow bags can dry out in less than a day, but rot is essentially what happened. I could see that the burying of any of the vines or leaves was just destructive. Natural potato behavior aside, vines may tolerate being covered, but they sure don’t seem to like it! All my attempts at regular and sweet potatoes in raised beds (keyhole garden beds) and in the ground, are still producing plants (third and fourth generations) regardless of my attention.

I have used the wire tower method 3-4 times, and last year was my most successful yet. I planted 2 lb of seed potatoes. I harvested 18 lb red chieftain and 10 lb Russian blue. I think this is more than I could have grown in the ~5-6 ft^2 with traditional hilling but am not sure. I do agree with the articles premise that towers where potatoes only grow out the top, and the tower is made taller, provide no advantage over container growing. But I’m fairly confident the wire towers. If prepped correctly, can increase yields since plant foliage can cover the tops and sides of the wire cylinder.

Yup, I got sucked into the PT idea, tried it for 2 years, and this article is exactly right. I’ve turned the 4 level PT into two “containers” that now sit at the end of a raise bed. Yields are exactly the same, and my observations match exactly with the authors: potatoes grow about 6 inches above the seeds potatoes and that’s it. And actually, we planted in containers last year and got better yields than the PT ever did. Thanks for the article, good to read something truthful for once – Mike in Maine

We put our first tower out in 1973. Using four large tires, we continued to add enriched sandy compost as soon as the foliage reached six inches above the tire. It was an experiment. Using the latest maturing potato I could find, we managed to get the plant to grow close to forty drive inches. Quite an accomplishment since the ones growing in the garden only made it to 20″-24″ by late October.

With great anticipation we careful removed the first tire. There were small hair roots and one stolon. The second tire was removed to show larger roots and the starts of three more stolons. The third tire had two tubers larger than a jack ball. Half a dozen stolons were present, but looked rotten.

The last tire held the greatest suprise. A whopping seven tubers almost as large as a marble were scattered around the inside of the tire. They were rubbery as if they had been overheated and started cooking. The roots were stunted and much smaller than I had anticipated. The thirty foot row next to the tire tower averaged ten pounds per plant.

Sure that I had did something wrong I tried planting in a wire tower, a barrel, a box that had boards added with soil carried to the top, deep hay over the rows.

Over fifty years later we still plant three forty-seven foot long beds. We moved from Virginia sandy soil to Missouri rock/clay dirt where we still plant potatoes into the rocks and cover with old hay.

I tried the cage and straw tower once and got basically nothing. When I planted potatoes in raised beds, I got a year’s worth of potatoes, red, long white, purple and Yukon gold. I just bought potatoes in the store, cut them into chunks with an eye or two on each chunk, let them dry overnight and put them in the ground. I have read that this is impossible, but it worked for me. Towers don’t.

By reading most of the comments, I have found that my yields were no more than if planted in my raised bed, however, I did find that the only benefit of a tower is that most of the time, it allows most of the smaller potatoes to grow bigger thus giving the appearance that the yield was larger.